A Pokémon Adventure

POST MORTEM

16 min read

In 2025 I had the opportunity to spend some months living with a 6 year old absolutely obsessed with the Pokemon card-trading game, and didn’t know how to play.

He kept asking again and again tonplay the game with me and so finally my game designer caved in: “What if my made a game to teach him how to play, while getting inspired by RPG and roguelite mechanics to immerse him in a story and world, provide diversity and replay value, and introduce him to the basics of deckbuilding ?”

The Pokemon franchise was one I hadn’t been immersed since when I played the first and second generation of games on my gameboy-color, in the early 2000s, and I had a lot of catching up to do.

Pokémon cards then vs. now: We have a alot of catching up to do.

Designing the MVP:

Intentions:

Introduce the mechanics of the game progressively so a 6 year old could understand them.

Provide great diversity and replay value.

Introduce basic deckbuilding.

Immerse the player in a narrative adventure of which they are the hero.

Challenges:

A great number of cards to get familiar with.

Some cards can be complex to handle for the reading comprehension of a 6 year-old.

Many cards evolve from other specific cards; it is not as easy as putting a card in the deck and playing it.

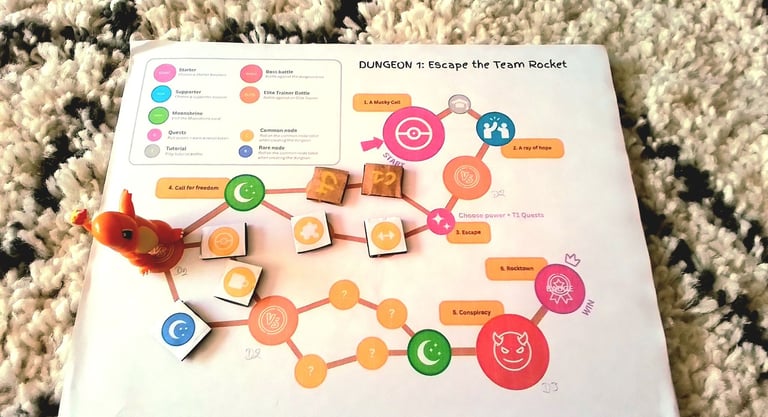

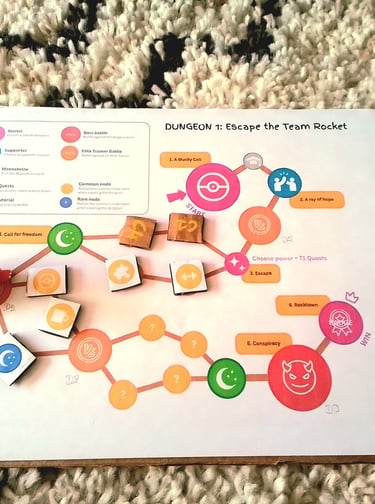

Initial solutions: Dungeon TIERS, boosters, and game extensions.

My first inspiration was taken from the roguelite dungeons featured in one of my favourite digital card games in recent years: Legends of Runeterra. There, the player moves through the tiles of a semi-randomly generated dungeons, making choices about where to go, battling foes and growing their deck on their way to the final boss (with a mid-boss on the way).

Legends of Runeterra: One of the major inspirations for the MVP of A Pokemon Adventure.

I decided this design was a great place to start with; and could figure out how to adapt it to the specific needs of the pokemon card game deckbuilding, and enhance it with a deeper narrative experience (pretty much absent from the LoR version).

In order to progressively introduce complexicity, I decided to divide the adventures in tiers. Some adventures would happen in tier 1 & 2, and others in tier 3 & 4, which would limit the experience like this:

Tier 1: features only basic and stage 1 pokemon.

Tier 2: adds stage 2 pokemon.

Tier 3: adds EX & V pokemon.

Tier 4: adds Vmax, Tagteams and Mega pokemon.

Tile-based dungeon exploration in the early A Pokemon Adventure prototype.

I decided to remove the EX and similar pokemon from a beginner’s playthrough because the cards add more rules and tend to be more complex than others, with added abilities, once-in-a-fight attacks, etc… There are also a ton of fun theme decks to play that stop being viable as soon as you introduce such powerful cards in the game, and part of the fun of thisbgame experience would be, I figured, in playing with a lot of off-meta but cool cards which you would definitely never see in tournaments, but have a home in a more casual and story-driven adventure in which the player is mostly meant to win every match.

Rapid Prototyping with material on hand, (from left to right): real card, japanese card with paper translation, printed proxy card, doodled proxy card.

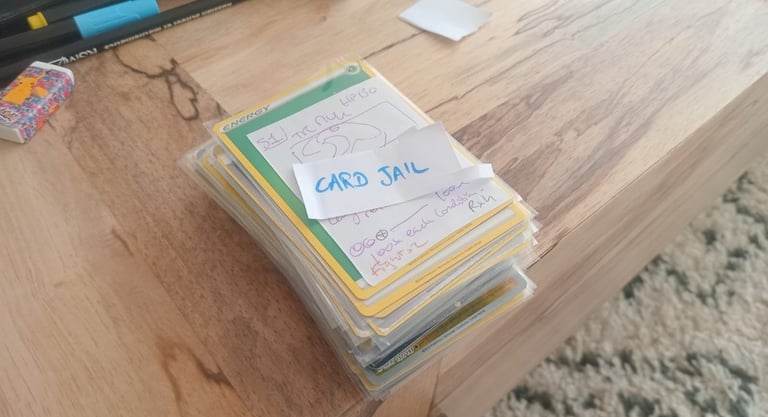

Rapidly growing pile of cards cut from the game because they were too weak, too powerful (for the game’s format and meta), not thematically relevant enough, or I realized I only wanted 1 copy instead of 2.

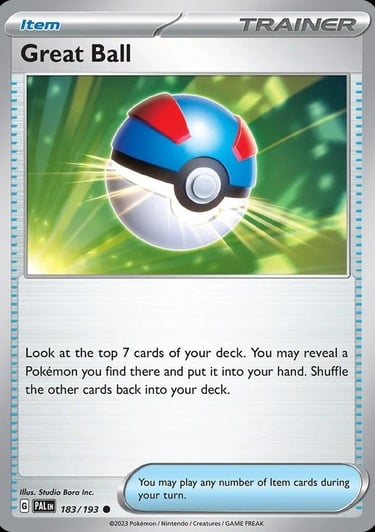

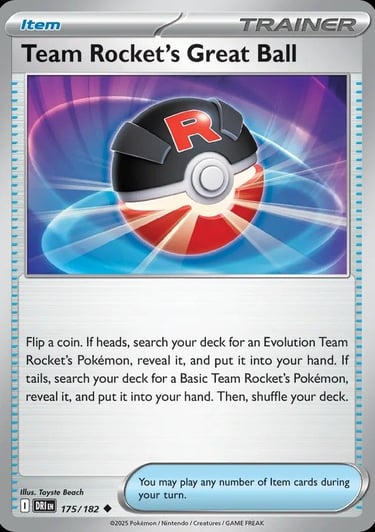

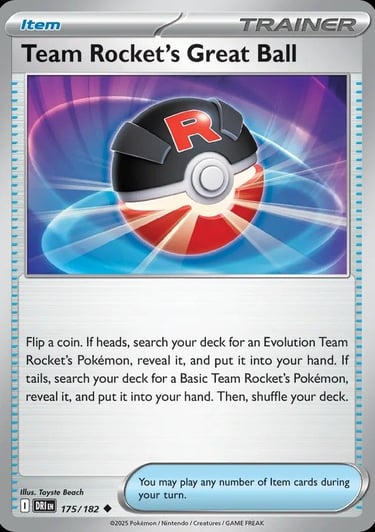

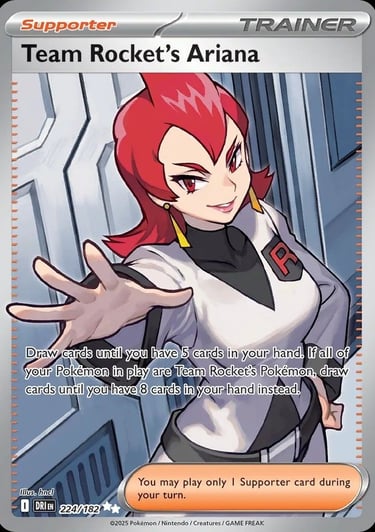

Something I did to help me as a designer early on was to restrict my search to a few extensions only. The latest expansion at the time: Destined rivals, was focused on the iconic Team Rocket; perfect - I could build a few Thematic decklists from this set only. This one and a couple other extensions would be the foundation for my early deckbuilding exploration.

Weak trainer cards were perfect for thematic early dungeon enemy encounters. They are able to shine in an environment where it’s okay for them to lose.

Additional restrictions which would both my search and the dreaded final boss of any board game - aka the amount of cards in the box - was to limit each adventures to using only 4 out of the 8 energy types, thus limiting the diversity of energy cards (which can rapidly bloat the number of cards) and available pokemon (creating some focus in strategies).

To complement this, I decided - instead of playing with the classical 60 cards deck with 4 max copies of each card - to start the game with around 20 cards, and get more cards along the way, with a maximum of 2 copies per card.

Trying to select enemy encounters by thematic relevance, excitement factor, and power level.

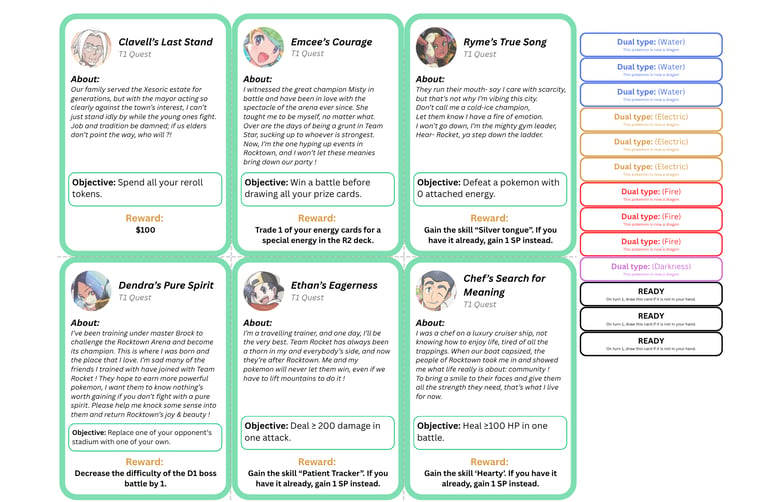

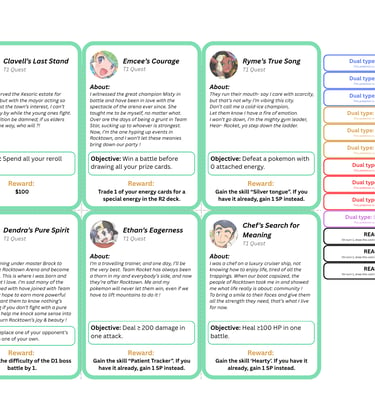

Supporter quests were a great way to provide optional narrative bits, hint at unconventional ways to play the game, and an additional lever to distribute rewards.

Spent some time beautifying the game boards while waiting for the first playtests; boon of working with an established IP. I also created custom cards using an online tool for special features.

To solve the problem of evolution cards, it seemed inevitable to have to package some cards together, but I didn’t want that to be the end of everything, and so I created a few added features:

Starter boosters: As a mandatory step in any of the games of the iconic franchise, the player would be granted a pokemon to be the star of their team, with a basic and stage 1 versions of that pokemon at the beginning of their journey, and for it to evolve to a stage 2 pokemon at the start of the second and final dungeon.

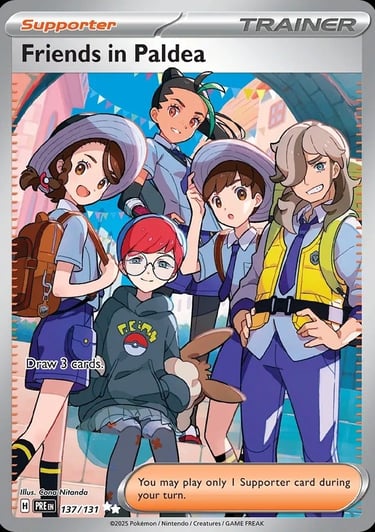

Supporter boosters: You are not alone on your journey, part of the pokemon identity is its focus on friendship. The player chooses a friendly trainer to explore the dungeon with, who come with their own supporter card, a pokemon and an item.

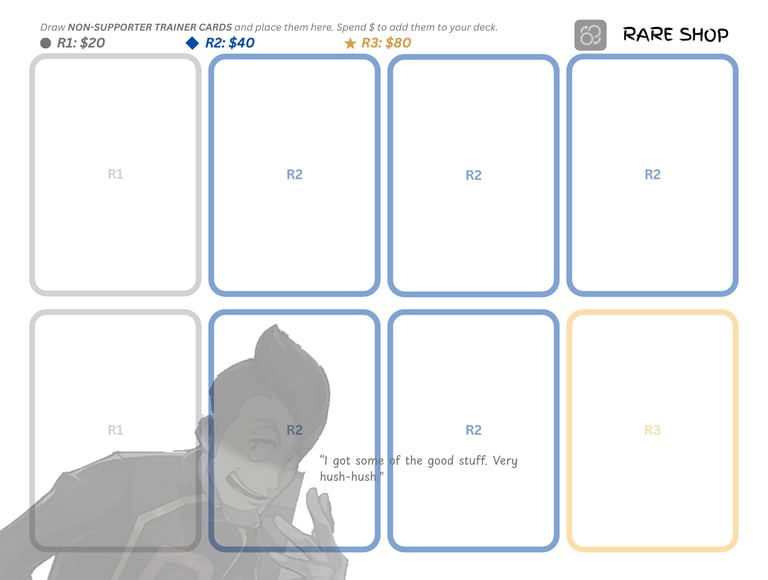

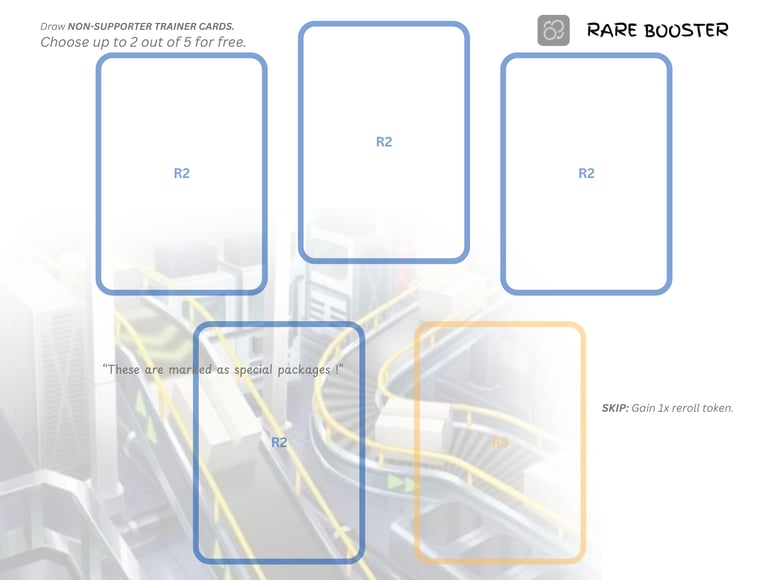

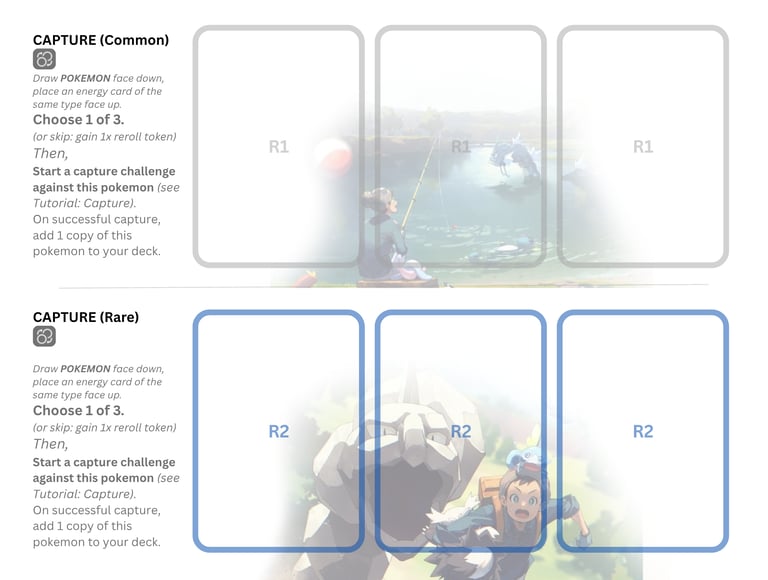

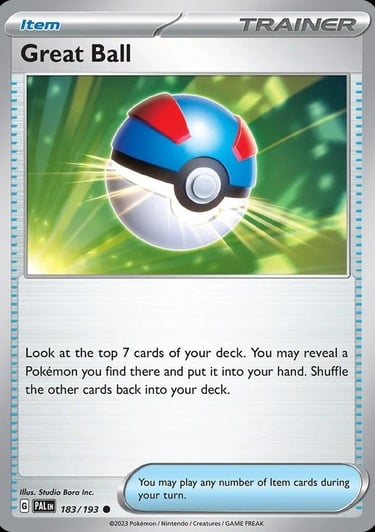

Boosters & shops: Are dungeon events in which the player can select additional item cards to add to their deck.

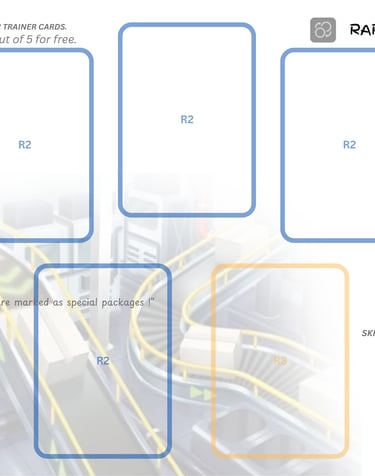

Wild pokemon capture: is a fun little combat challenge I designed to simulate the video game experience of stumbling on a wild pokemon, bringing it low in life and throwing a pokeball at it with a chance to capture it.

These would be the fundamental building blocks of the deckbuilding mechanics in A Pokemon Adventure, to which I added yet additional systems which roe was to provide consistency and reliable ways to build a good deck (I wanted this aspect of the game to be greatly facilitated so that a 6 year old could enjoy it). These were:

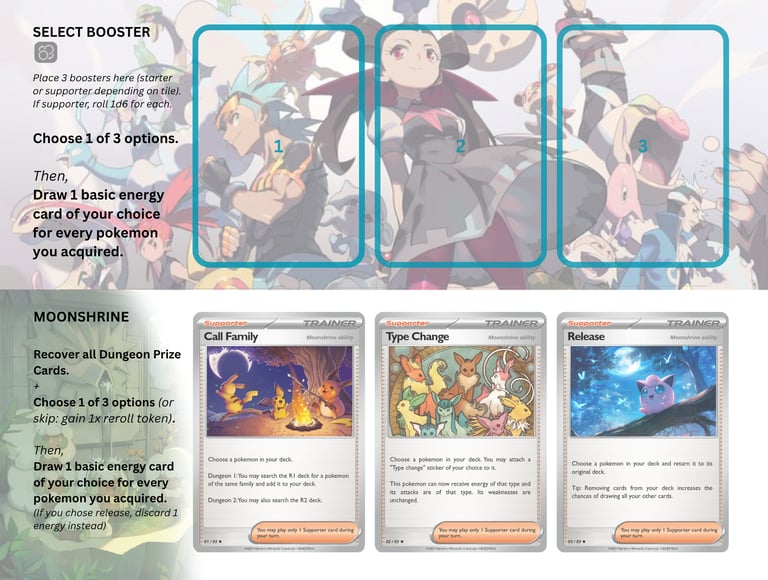

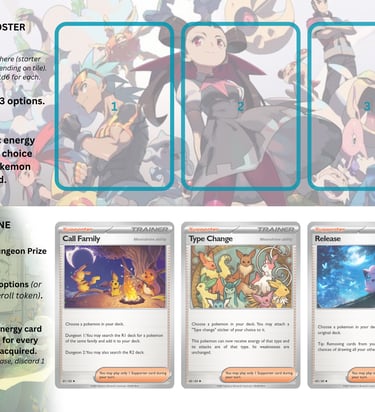

The moonshrine abilities: Moonshrines are the ’rest’ tiles in a dungeon, where the player regains health points and can choose one of 3 abilities to enhance their deck: 1. Call family: to select a pokemon in your deck and find more copies of it or its direct evolution in the random decks. 2. Change type: to adapt a caught pokemon to the energy cards in the deck and provide unique deckbuilding opportunities not otherwise found in the classic tcg. 3. Release: to remove a pokemon cardbfrom the deck - that ability would later become ’Call of nature’ to trade 2 pokemon in your deck for any 1 pokemon of your choice, after playtesting.

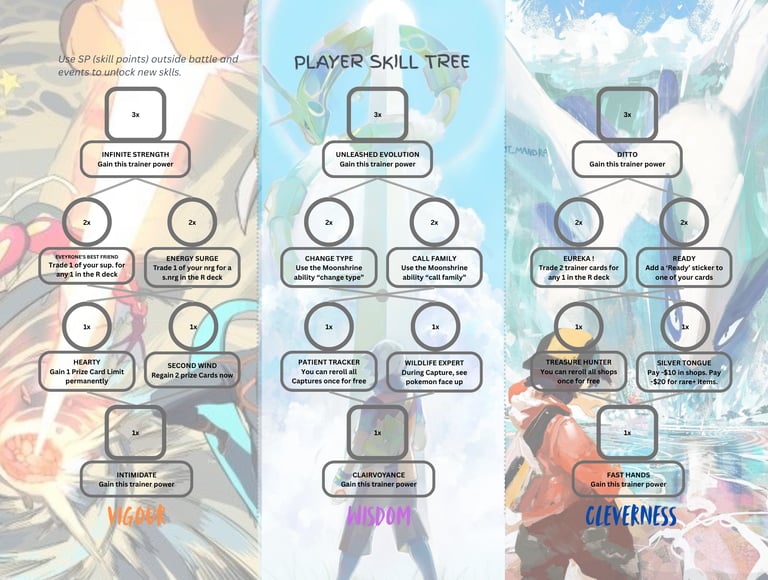

Trainer skills & The skill tree: Trainer skills are a feature I added to the game, which add personality and reliability to otherwise non-optimal decks. They are typically a Supporter card (which exist in the real tcg) put on the board, and can be drawn on each player’s turn in exchange for discarding a card in hand. It is like saying “Haha, I had the perfect card in hand all along !”. These trainer powers I found were a great way to fill the holes in a deck in terms of basic foundamentals such as draw, search, energy acceleration, swapping and healing. The skill tree itself would be divided in 3 branches: Vigour (focused on energy and supporters), Wisdom (focused on pokemon), and Cleverness (focused on items), qs well as tiers, with the first and 4th (final) tiers being a trainer power, the second tier about helping dungeon exploration (such as reduced price in shops or the ability to predict which wild pokemon will be encountered), and the 3rd tier helping with deckbuilding (such as the ability to trade 2 items or pokemon in the deck for any one of your choice).

A skill tree to add an additional way to create more reliable outcomes in deckbuilding through the acquisition of trainer powers, dungeon exploration skills and card-trading opportunities.

Reroll tokens: Allow the player to spend a resource to have a second chance when luck isn’t on their side during dungeon events.

Supporter quests: I was scared of adding in fear of feature creep, but turned out to accomplish a great many things at once: A. They provided a window into the stories of player companions. B. They hinted at using unusual game mechanics (such as winning in unconventional ways, taking advantage of enemy weaknesses to deal more damage, replacing an enemy stadium, or swapping pokemon to prevent a k.o.). C. They also provided an additional balance lever to distribute rewards to help the player with dungeon exploration or with deckbuilding.

Trying to recreate iconic moments of the pokemon video game and card game experience, like going to the shop, opening booster packs, capturing wild pokemon or trading them.

Opening booster packs (of items only) in A Pokemon Adventure is essentially justified as stealing the Team Rocket’s mail !

Creating a custom minigame to mimic the experience of capturing wild pokemon in the video game franchise.

Trading pokemon or stumbling upon rare items has always been a trademark of building a powerful team, and I wanted that aspect to be part of the game too.

Initial testing: problems and solutions.

The mark of a great designer is not to get it right the first time, it’s to know how to fix it when there’s a problem.

Before presenting the game to my young friend, I (wisely) took advantage of a few days I coud spend on my own to playtest the game. Thankfully, playing the tcg pokemon game was fun, exploring the LoR-like dungeon was fun, but there were a number of fundamental non-balance issues, especially in battle:

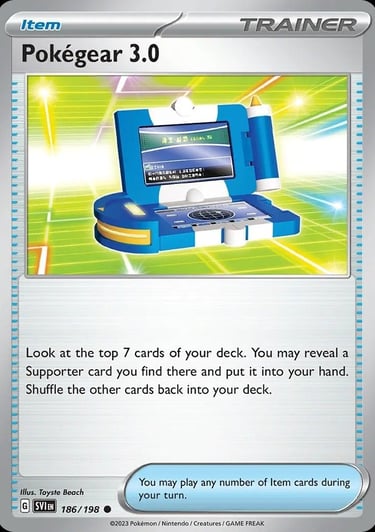

Both the player decks and the enemy decks suffered from too little draw engines and consistency.

My design to add random cards to enemy decks, with the intention to add variety, was backfiring, as the random cards, especially pokemon, seemed to pollute the decks more than add unexpected spice, and the discard opportunities I added with trainer powers did not feel like enough to solve that problem. Turns out, while most TCG decks can be thought of as a tree, with certain cards being used to handle the early, medium and late game, the Pokemon TCG deckbuilding resembles more a web, with a lot of searching features which build a ton of reliability into spiraling toward the perfect game state. This feature of deckbuilding is why, although it can be thought of as a child’s game, the pokemon tcg is actually one of the best current tcgs for competitive play, with randomness being much less of a factor than good decision making compared to other games like Magic the gathering; but it was also why my decks more often than not felt off.

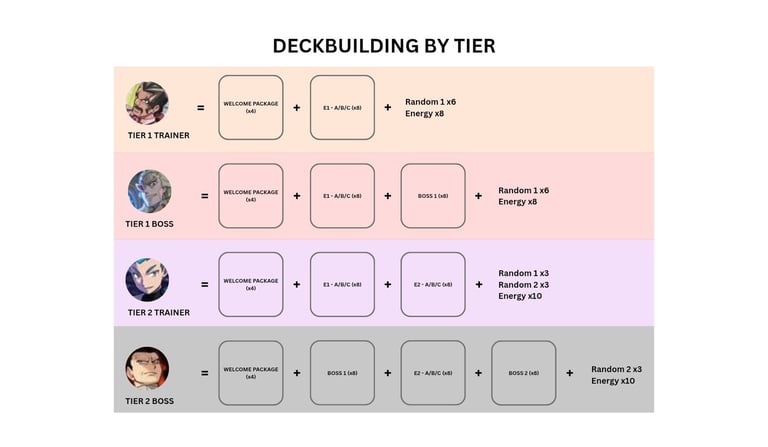

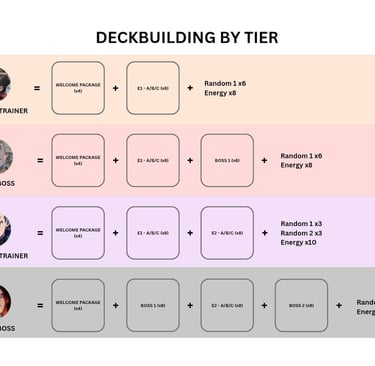

Solutions: the Rocktown Rebels and Team Rocket Welcome Packages.

To create both variety with a minimal number of cards and different levels of difficulty, plus the challenge of pokemon evolutions, I approched deckbuilding as if using building blocks, some of them being common to mumtiple decks.

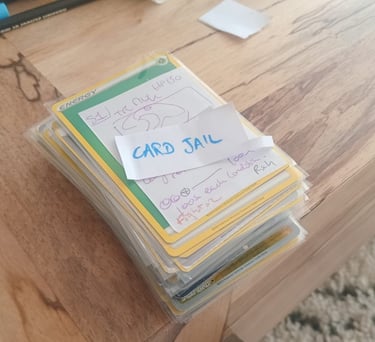

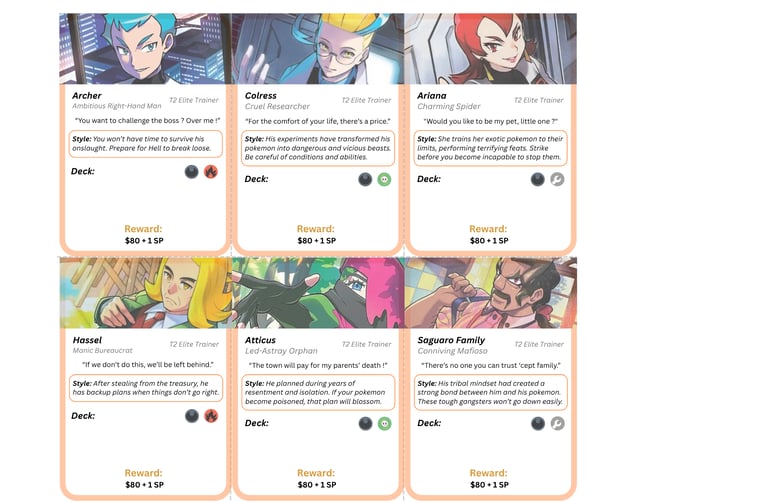

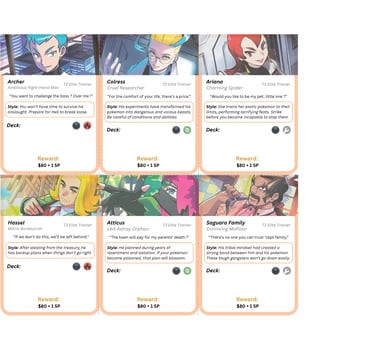

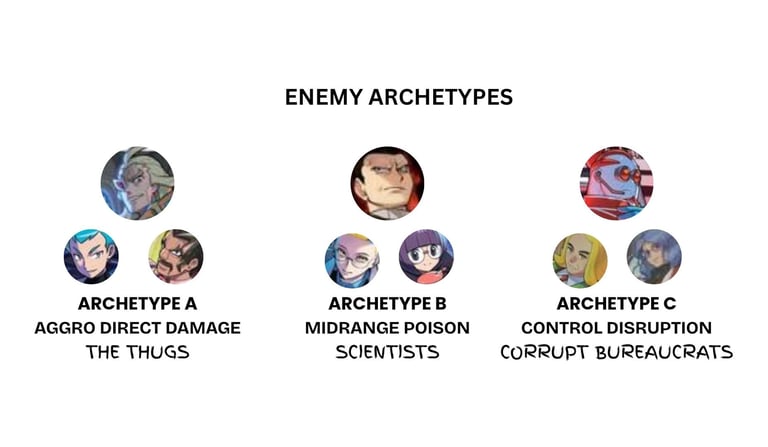

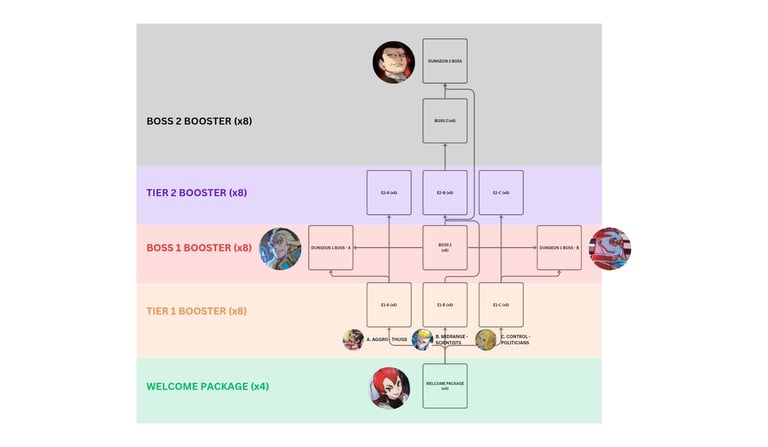

The enemy decks were separated into multiple archetypes: A (aggro direct damage), B (Midrange poison), and C (Control disruption), each with a tier 1 and tier 2 package, built on top of each other. Each trainer’s unique trainer power would add personality and a twist to each of these archetypes. This was working well.

To solve the consistency problem of decks, I decided to add a small package of 4 cards (later with 1 more coming in in dungeon 2) to both the player and the enemy decks that would add a number of search engines. These would be respectively be the Rocktown Rebels (for the player) and the Team Rocket (for the enemy) welcome packages. I loved this solution because it felt right on all levels: it instantly improved the reliability and feel-good factors of all decks, it reinforced the themes of both player and enemy factions, and narratively, it felt like the characters in these cards had life and were actively participating in the battles. A victory on all counts.

Additionally, I decided to put a limit to the max number of cards in a deck to 40 (there was previously no limit), a number that correlated well with the 2 max copies of a card in a deck. This rule instantly improved reliability in battles for player decks.

The Rocktown Rebels and Team Rocket Welcome Packages, each a set of 4 cards, were a great solution to the initial draw and consistency issue of both player and enemy decks, all the while reinforcing the themes and narrative immersion of battles.

Other Points of balancing:

The first few days of playtests included rapid iteration on the topics of number of cards in boosters and decks, finding the right balance of pokemon-trainer-energy for this special format of the game (20-40 cards instead of 60, and off-meta picks), pokedollar and skill points economy, swapping, adding or removing certain items and pokemon for balance reason (such as a pokemon who uses the weakness of 90% of the enemy pokemon which are dominantly darkness type, making the game’s strategy too straightforward).

Creating enemy archetypes for deckbuilding based on playstyle and theme.

Incremental deckbuilding achieved with boosters serving as the building blocks for enemy decks.

Other way to picture deckbuilding with boosters serving as building blocks.

Design choices that provided both a great challenge and felt right to keep:

I wanted each card to be unique to the booster or package it was a part of. That meant that staple cards in the meta for fundamental deck functions such as search and energy acceleration were not accessible to most deck. Instead, each deck would have to find ways unique, often unconventional ways to solve basic problems. This required I become a lot more familiar with the pool of cards available and the rhythm of games, but doing so was worth it, with each deck in the end feeling very distinct, and the narrative coherence of the experience being preserved (of course the same character can’t be both your friend and your foe simultaneously !). Plus it had the practical effect, for a physical game, that the cards were easier to order and separate.

The reality of making this a board game instead of a digital product definitely brought a lot of constraints, and at some points the game felt a bit bloated with multiple boards or deck boosters to assemble and deassemble between battles. Even though, because I was making this game for a 6-year-old to have fun with his card collection, and because it was meant as a prototype, I did not want to involve screens.

Still fits in a regular size box. Objective fulfilled.

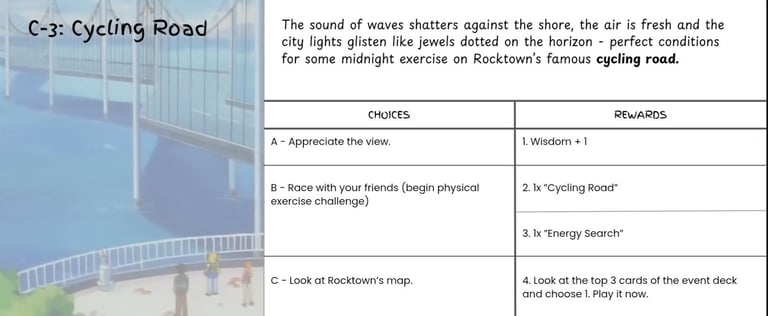

Feature experimentation: Event cards.

Now comfortable with the general experience and balance of the game after thourough solo paytesting, I decided to experiment further with different aspects of the game.

One feature I was particularly keen on exploring was one which had come from a previous dungeon exploration boardgame concept I had made years ago on the project ‘Adventure Lite’ called “event cards”.

Instead of having a tile-based exploration system in which the player could choose between going to a shop or capturing a pokemon, instead, there would be a deck of events the player could draw and stumble upon, in which they could make decisions that would lead to acquiring what they are interested in. The experience would be far more narrative and immersive, but also less gamey; in good and bad.

One aspect that always jumps to me in these kinds of of choices when they appear in game is the insurmontable gap between what I would choose to do as a character and what I would choose to do as a player; this conflict can more often break rather than make coherence and immersion. Another one can be a felt loss of agency in the exploration part of the dungeon; As a player, I no longer choose my path, I draw cards.

I first decided to create a hybrid model, in which half of the events would be drawn from a deck and the other half explored on tiles. This added a bit of clukiness as I needed physical space for both of these systems on the game space, but was a good way to get an emotional comparison.

While the game was fun to play on its own with just tile exploration, after experimenting with event cards, it felt hard to go back to the previous system. Event cards undeniably added a sense of immersion and emotional depth which was not present in the previous version; and, ultimately, it checked the mark for what I had set to achieve in the firsg place: making the player like they are part of that world, a’d the hero of their own adventure. In fact, the tile exploration was born from a desire to create a lean system-light MVP with fast games, and the event deck was bringing the experience closer to what I had first imagined: something closer to a pen&paper role playing game with a semi-long campaign featuring tcg battles, that could emulate the kind of feeling I had felt while playing the fiest couple pokemon videogames in my childhood. I was moving through the city, exploring a forest, meeting people and pokemon in life-like situations and making decisions about them. That felt good.

Rough drafts for testing the event cards feature - mixing pen & paper mechanics with the roguelike formula.

Print test to gauge what a final event card could look like, with the amount of text and type of narration permissible in that media.

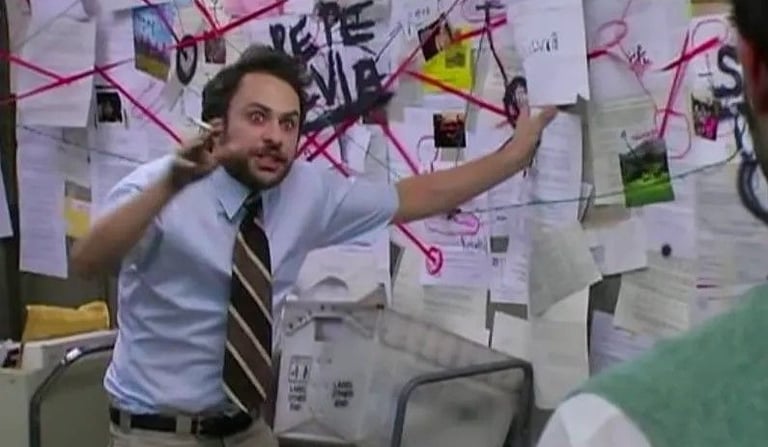

Designing the final boss battle

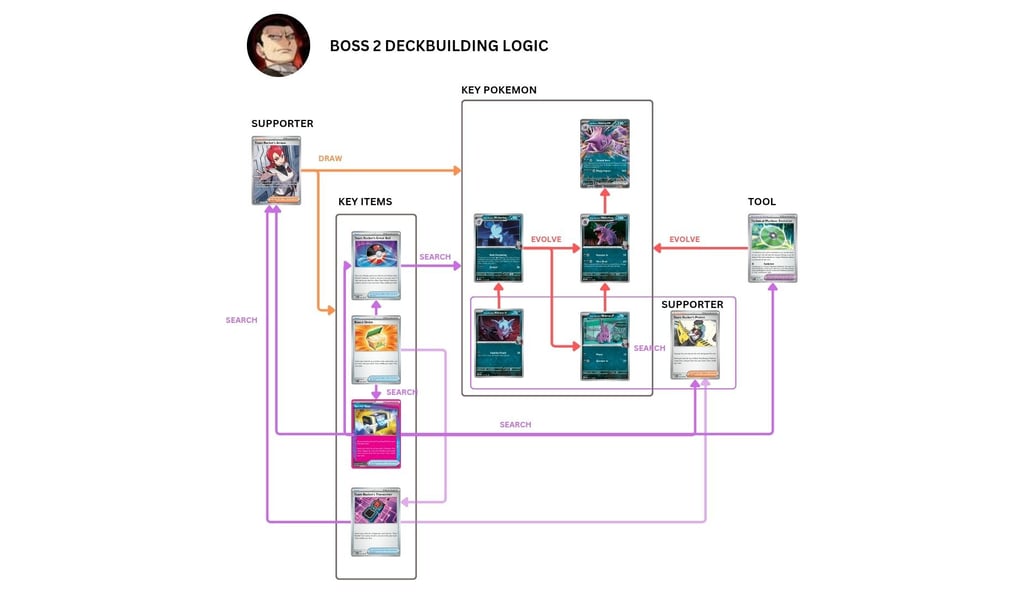

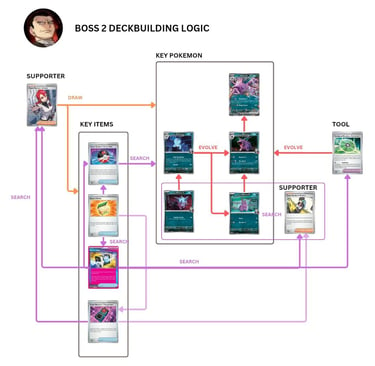

The strategy for the final boss battle was pretty straightforward: Get Nidoking EX (the only EX card in the game ! A fitting challenge for the last battle) out on the board as quick and reliably as possible.

The final boss battle would be the point of focus for game balancing of final player decks, it had to feel good to play against, reliably. That point of reliability was the point of struggle in the initial boss deck, itself a composite patchwork of multiple booster packs.

I had to become creative with the solutions I could bring to fix this. That challenge was made all the more difficult bdcause of the design rule I had put upon myself: the same card can only be found in one booster pack; this meant that the common meta picks the game is balanced around were sometimes locked in a booster only available to the player, or another enemy one, and the boss had no access to them. I went to scoure pokemon tcg databases for sometimes obscure off-meta picks that could fit the bill, all the while distributing these cards in the different boosters the boss 2 had access to, in a way that was thematic and balanced for the other decks using these same boosters.

Me upon hours of playtests, looking at pokemon tcg databases, and many obscure cards, to make the boss 2 deck work mechanically, thematically, feel fun, balanced and above all - reliable.

I did arrive at a deck that fulfilled all these conditions, sometimes too well. I had to make decisions to resolve conflicts between strength, theme and reliability. In the end I decided that reliability was the ultimate factor to protect; in my hours of playtests, winning against the boss in a few turns because they had a bad draw was by far the most anticlimactic and unpleasant experience that could happen. Eliminating that possibility was priority n°1.

The web-like design of a pokemon deck, including lots of draw and searching tools to spiral toward the ultimate goal: evolving toward Nidoking EX, the star pokemon of the boss.

Key takeaways:

When thinking of solutions, think not only in terms of balance but also of excitement: what would be a cool experience for the player ?

Limitation is a friend of design.

Some design choices are worth sticking to despite intense time demands or initial clunkiness if they help making the game more distinct, coherent, and fun.

When multiple design choices are conflicting with each other, imagine multiple versions of the game: one for minimal development complexicity, one for maximum player enjoyment. Which one is worth making at this time ?

Random is not always a good way to build diversity and replayability. Sometimes random cards just pollute the deck with unusable bits; on a bad draw, this can make the deck unreliable - for a boardgame where’s there’s no way to cheat with the draw, that can be a death sentence for an enemy deck and the player experience.

A real badge to reward the player upon completion of the first dungeon given in the story hy the Rocktown Rebels. This allows the player tk control Stage 2 Pokemon. A cool way to build excitement, belonging and friendship, and distribute mechanical rewards all in one.

Thank you for reading !

Connect

Let's collaborate on your next game design project:

damien.f.rodriguez@gmail.com

© 2025. All rights reserved.